Icon NOW: Jakkai Siributr Unravels Ambition into Compassion

Icon NOW: Jakkai Siributr Unravels Ambition into Compassion

วันที่นำเข้าข้อมูล 22 Nov 2021

วันที่ปรับปรุงข้อมูล 30 Nov 2022

Icon NOW: Jakkai Siributr Unravels Ambition into Compassion

What’s in an icon? As part of Thailand NOW’s mission to share authentic insights into all things Thai, we’re spotlighting iconic individuals who have not only excelled in their respective areas, but influenced the complex tapestry of Thailand as it exists today and, in doing so, inspire us to be a part of the fabric of Thai society.

In this Icon NOW interview, Jakkai Siributr, one of Southeast Asia’s leading contemporary artists, opens up about his journey through textile art and how life, little by little, shaped him into the person he is today and guided him to what he was meant to be doing all along.

There are some insights that only come with age.

That’s the key takeaway of our conversation with Jakkai Siributr, who had secluded himself in his Bangkok studio with the sometimes-exuberant company of his rooster. The veteran artist has spent a lifetime making sense of the world and his life through his artwork, which has, in turn, touched the lives of others in so many ways.

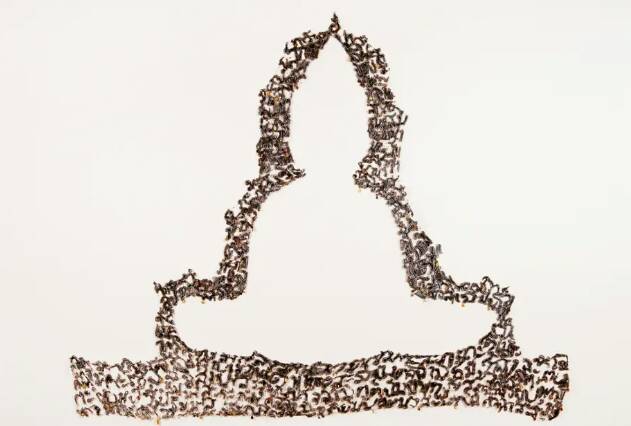

A regular at many top art galleries around the world in both solo and group exhibitions, Jakkai is internationally recognised for meticulous textile artwork and installations that convey powerful messages about religion, society, and politics.

While his body of work has earned the artist critical acclaim, it’s only later in life that he found his true calling.

“I literally grew up surrounded by textiles.”

Born and raised in Thailand, Jakkai was cared for by his family’s long-time nanny, who never threw away worn-out clothes. Instead, she would constantly mend old clothes or repurpose them, sometimes as pillowcases. Meanwhile, his aunt would offer batik painting courses on the weekends, which in 1970s Thailand, was seen as somewhat unconventional.

“I literally grew up surrounded by textiles,” he says.

At the age of 15, his parents sent him to finish his education in the United States, and when it came time to pick a university degree, it was no surprise that Jakkai chose to major in textiles.

“Back then, my skills were just average,” he says. “I didn’t even think about being a professional artist. Seeing my aunt and her business, I thought it may be possible.”

Having earned a B.A. in Textile/Fine Arts from Indiana University and an M.S. in Printed Textile Design from Philadelphia University, he returned to Thailand in 1996 and received an invitation to teach aspiring designers at Thammasat University.

For the next eight years, he led several field trips across the country, which he found as educational for him as they were for his students.

“Had I gone to school in Thailand, I would have seen and understood the local lifeways, but I left Thailand right after junior high,” Jakkai explains. “I was too young to grasp several Thai traits… We went to every region in Thailand. I see how people lived and what they made for clothes.”

Collection of Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Nonetheless, after eight years of lecturing, Jakkai decided to pursue his work as a full-time artist. He admitted that his focus at that time was to be “successful” and have his works presented in major galleries around the world.

“With such ambitious goals, of course there were disappointments,” he says, smiling. “Back then I was always comparing myself to other artists. Why did they get this and I didn’t?”

Despite his private disappointments, Jakkai achieved exactly what he set out to do. His pieces have been featured in international art museums spanning New York, Turkey, Taipei, Bangkok, and Brisbane. Notably, his 2010 solo exhibition, “Karma Cash & Carry,” portrayed a karmic convenience store, and his 2014 solo exhibition, “Transient Shelter,” which The New York Times saw as a critique of the “earthly trappings of prestige.”

And yet, events later in his life would help him to realize different goals.

“…through stitching, I understand mindfulness…”

The relationship between trauma and embroidery is not immediately obvious; few other artists may have seen the connection.

In 2017, Jakkai initiated a project with women in the three southern border provinces of Thailand who had lost family members due to sectarian violence. Through needlework, the ladies were able to tell their painful memories.

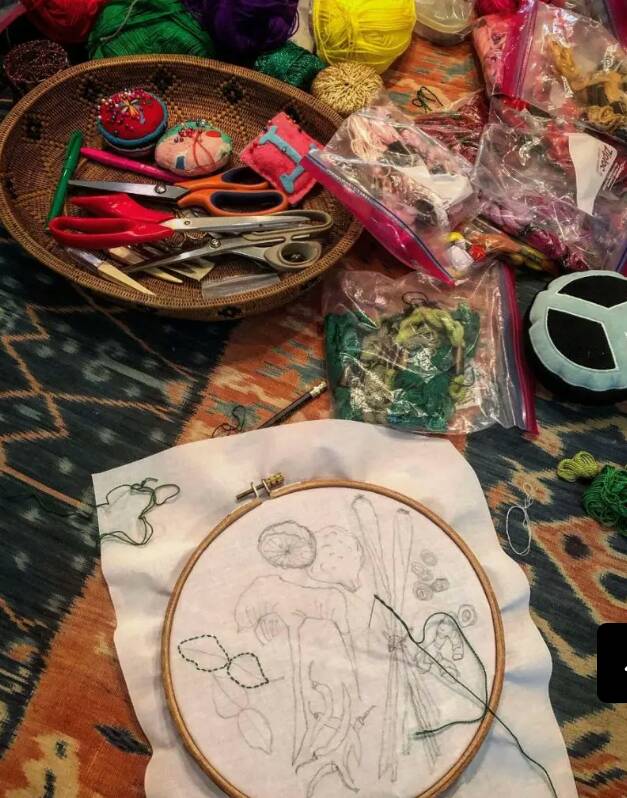

Shortly after, he was invited to visit the university he attended in Indiana, holding a storytelling embroidery workshop for refugee children. The children were encouraged to work through their memories and traumas using needle and thread.

“I have some children saying stitching really calms them down and they do it before going to bed. Embroidery may not be an answer for everybody, but for some, it is a real therapy. You don’t need to tell your pain verbally if you don’t want to,” Jakkai explains.

“Embroidery is repetitive. You go up and down. To me it’s kind of meditative. I cannot really meditate. But through stitching, I understand mindfulness and appreciate having it.”

When his beloved mother passed away, Jakkai did what he knew: created artwork using her old clothes.

“Clothes are tactile,” he points out. “They give you a sense of connection with their owners, a special kind of warmth and something to help you cope with grief and loss.”

When his friends went through similar feelings of loss, the textile artist helped them to create something from the clothes of their loved ones.

“At my age, many of my friends are losing their spouses or parents,” Jakkai explains. ”It’s very personal. Each of them has their own way to cope with grief and loss.”

With his mother’s passing, the veteran artist found himself reflecting on his mother’s words. Since he was a child, she had worked to help the less fortunate through her charities and foundations.

“She would always teach me that since we have comparatively more opportunities and resources, we are therefore obliged to contribute to society as much as we can,” he recounts. “I think all those factors have shaped me into what I am today.”

Collection of Royal Thai Embassy Maputo

As if to drive the point home, his next watershed moment would come in 2018, when then-Thai Ambassador to Mozambique, H.E. Russ Jalichandra, invited him to create a piece for the Royal Thai Embassy in Maputo.

There, he spent time speaking with locals and exploring the nearby shantytown. Having received most of their everyday clothes through humanitarian aid, the nearby communities had plenty of local seamstresses who found work adjusting and mending second-hand clothes.

Jakkai decided to hire the local seamstresses—many of whom were the wives of embassy chauffeurs—to assist him on the project. What touched him was that their husbands would also come to help at the end of their shift.

“These are the people who have zero experience with art. It was fantastic and heartwarming. I have never felt anything like that before,” he recalls.

After three weeks working with local Mozambicans, Jakkai said he came back to Thailand with a new perspective.

TARs Gallery

Like many other artists, Jakkai has experienced postponements and cancellations during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, he sees it as the most productive period in his career and an opportunity to pursue another project.

To help a marginalised community in the upper northern province of Phayao, Jakkai started Phayao a Porter, which hires local seamstresses to produce embroidered pieces for sale. Thirty percent of the proceeds are funneled back into the community, in addition to fair wages paid to its workers—something they had never received before.

“I went there and saw how much they received for their work. They were paid less than 10 Baht for making one pair of pants. That’s not right. It’s not a fair rate,” the artist declares.

As he turns his attention to more fulfilling, collaborative projects, Jakkai’s views and priorities have changed a lot since his younger days.

“It really comes with age,” he says, smiling as he reflects on his earlier, ambitious mindset, where he often sought validation by comparing his success with other artists’.

“I now realize that each individual’s journey is only specific to that person and that they cannot be compared. And I would not trade my life for anyone else’s regardless of their wealth or successes.“

The most important thing is you have to accept yourself and be grateful for it. It’s one of the most difficult things to do. If you can do it while still young, that’s great.”

สถานเอกอัครราชทูต ณ กรุงเตหะราน

Office Hours: Sunday to Thursday, 08:30-12:00 and 13:00-16:30 (Except public holidays)