Artistic Thai Lacquerware Invokes Baroque Style

Artistic Thai Lacquerware Invokes Baroque Style

วันที่นำเข้าข้อมูล 25 May 2022

วันที่ปรับปรุงข้อมูล 25 May 2022

The word “baroque” might make you think of the Palace of Versailles or the Vatican. Afterall, it’s a European term used to describe a very vivid period in European art. Yet Siamese art and Italian churches have much more in common than you might think.

“Baroque” describes art and architecture that expresses grandeur and drama, playing with older motifs in new and creative ways. It ignores realism in favor of visually compelling imagery. These characteristics of the baroque style could be used to describe a number of European Catholic churches, Renaissance paintings—as well as Siamese gilt lacquerware.

Chart the history of Siamese gilt lacquerware and how its rich motifs have influenced modern Thai design.

What is gilt lacquerware?

Gilt lacquerware consists of a dark lacquered surface with designs in gold leaf. The medium appeared some time during the late-16th to early-17th century and has been used to embellish cabinets, chests, and window or door shutters.

The process is tedious, requiring great artistic skill. Sketches are first made on paper, and then transferred onto black lacquered wooden boards. A negative image is painted in a yellow, water-soluble paint called kamalor, and gold leaf is applied to the unpainted sections.

Finally, water is poured over to remove the yellow paint and excess gold (hence the name lai rod nahm or “poured water designs”) revealing a surface full of rich gilded details that invites closer inspection.

Before baroque

Prior to the golden age of lacquerware (roughly mid-17th to mid-18th centuries), designs were generally more formulaic and less complex. The most popular design used is the Kranok motif (also, kanok). Derived from nature, it was used on anything from stucco and paintings to woodcarvings.

The temple of Wat Lai in Lopburi province has a good example of mid-Ayutthaya ornamentation, where the motifs are confined to a framework.

A stucco panel from the ordination hall of Wat Lai. The designs revolve around a set geometric framework, filled with scroll designs. Source: Aiken Unni

Eventually, the focus would shift from narrative art to fully floral designs. This shift was likely due to prosperous trade and diplomacy with the Mughal and Deccan courts of India, whose art shows a similar fascination with nature.

The early decades of the 17th century produced some beautiful proto-baroque paintings and carvings. In Wat Chaiwatthanaram, Ayutthaya province, paintings dating to the temple’s construction in the reign of King Prasat Thong (1628–1655) have been preserved. Generally, they consist of kahn khot, or scrollwork, permeated by Kranok and floral motifs.

Murals in the Meru (towers) of Wat Chaiwatthanaram. The geometric framework seen at Wat Lai has given way to a looser aesthetic. Source: Aiken Unni

However, it was in the lacquerware cabinets of the same period that a full-scale baroque would emerge.

The gilded age

Usually kept in temple libraries or private collections, these gilt lacquerware cabinets weren’t constrained by political or religious agendas, setting the stage for Siamese baroque to blossom. While many pieces depicted scenes from the Himavanta, a mythical Eden-like forest underneath Mount Meru in Buddhist cosmology, artists began to experiment with painting animals, plants, and landscapes.

Working with gold leaf is inherently grandiose, so perhaps the medium naturally lent itself to the baroque style. But many pieces show a compulsive need to fill the entire area with these gilded details (lest the work be bland).

This manuscript chest from the national museum in Bangkok leaves no spare room between the major figures. It is filled to the brim with Kranok and floral designs past the point of realism.

Manuscript chest chest from the Bangkok National Museum. It depicts Garuda, Nagas, Japanese Baku-like animals, and other flora and fauna. Source: Aiken Unni

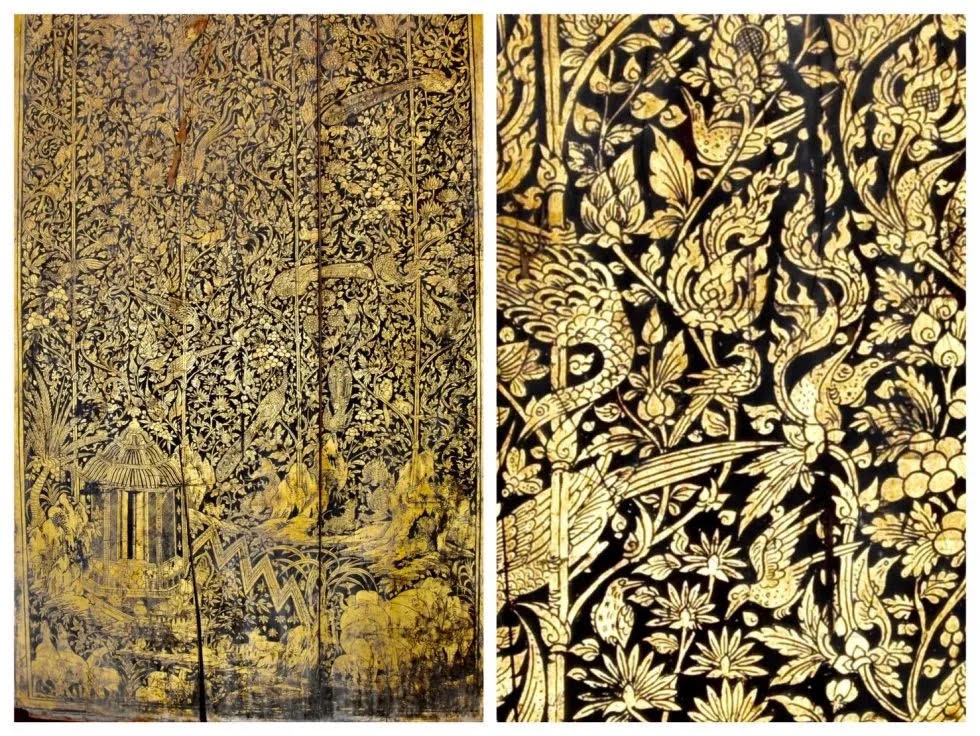

Wat Sala Pun in Ayutthaya still has a fragment of a cabinet depicting a very rich, abstracted scene. Between the maze of flowers and Kranok, however, there is a playfulness in the frolicking animals.

Squirrels chase each other, grabbing at one another’s bodies. Birds and peacocks in amorous pairs hide behind the flowers and leaves of the never-ending forest. Monkeys swing from branch to branch. The entire panel is like a game of hide and seek, challenging viewers to count all the animals.

Panel from a gilt lacquer cabinet from Wat Sala Pun. It depicts an ascetic at a pavilion, with flora and fauna above. Source: Aiken Unni

The modern age

Source: Wasu Watcharadachaphong / Shutterstock.com

These baroque elements of Ayutthaya’s golden age have survived into modern Thai art and design. You just have to know what to look for.

During the second half of the 18th century, these gilded designs became less intricate and more structured due to changes in taste and demand. A diamond trellis pattern became the standard by the start of the 19th century. Artwork featuring narrative scenes would become more common than purely ornamental or playful scenes of mythical creatures.

All through these changes, the Kranok motif continued to remain a favorite of Siamese artisans and has come to be seen as the very essence of Siamese art.

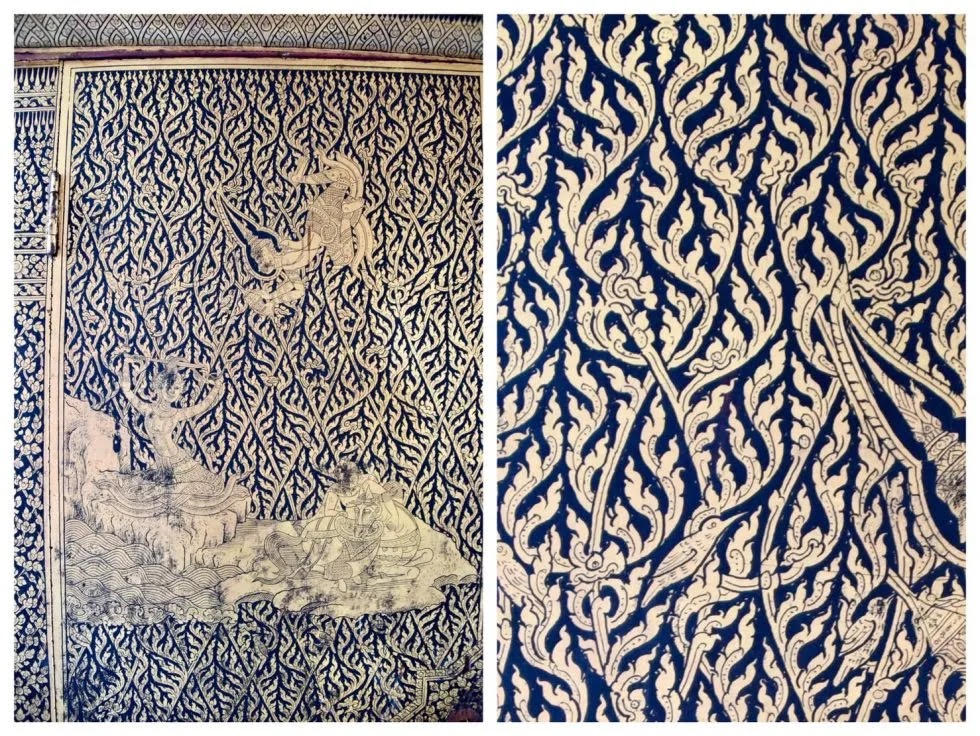

Kanok would continue to be used amongst these modern styles in a pattern called khreua thao. Gilt lacquerware on the whole has persisted as a courtly artform until the present day.

Lacquer cabinet with scenes from the life of the Buddha on khreua thao, dating to the first half of the 19th century. Currently in the possession of Wat Phichaiyatikaram, Thonburi.

Source: Aiken Unni

Due to its regal reputation, its context has extended outside monasteries and palaces. Today, you’ll find these timeless designs and motifs recreated in hotel lobbies, restaurants, spas, and even malls. They represent a certain nostalgia for Siamese history, evoking the very essence of Thai art for travelers.

Legacy of Siamese baroque

Siamese gilt lacquerware is synonymous with Siamese art and history. Despite its uncertain origins, we do know that the artists of Ayutthaya used it as a means of artistic expression, free from the limitations of religious or political usage. In doing so, they were able to create a new and interesting visual language.

The legacy of these achievements is two-fold: the first would be the unmistakable foundation that the baroque style provided for later lacquerware and then modern Thai design. Artists, for a time, would stray towards a less inventive style, but maintain a richness of detail and the various motifs inherited from the Ayutthaya artists.

Secondly, the term baroque can be expanded beyond its Western origins to describe Siamese art. Its inventiveness, dramatic style and richness rival those of baroque European art. Its complex history has led lacquerware motifs to become iconic imagery in Siamese art.

สถานเอกอัครราชทูต ณ กรุงเตหะราน

Office Hours: Sunday to Thursday, 08:30-12:00 and 13:00-16:30 (Except public holidays)